A great artist is always before his time or behind it.

George Moore

If tragedy, suffering, bigotry and depression create the fodder for great literature, is it any wonder that Ireland produces so many great writers, poets and playwrights?

During the Dark Ages, Ireland shielded the written word against the barbarism of the Roman Empire’s decaying ruins and became a haven for scholars seeking knowledge and enlightenment. They travelled from Rome itself to learn from the St Edna on Inishmore, and hundreds like him spread throughout the furthest corners of this Celtic island. A candle of hope that flickering behind the dark curtain of ignorance but once pulled aside its light flooded into the empty space to illuminate the known world again.

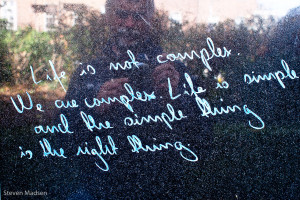

The great Irish writers shone that same light on their Nation’s struggles from the searing satire of British colonialism in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels to the brutal poverty in Frank McCourt’s memoirs, Angela’s Ashes and ‘Tis. Most famous of all is Oscar Wilde; the flamboyant writer lampooned British upper-class snobbery, and delved deep into the darkness of man’s heart with equal skill and attention. Widely revered and quoted, his works are largely unread by the modern populace but Oscar’s words reach out from the past to skewer the facile existence of many modern lives.

One’s real life is so often the life that one does not lead.

Oscar Wilde

James Joyce gave us his opus, Ulysses a rambling retelling of Homer’s Odyssey through his Dubliners’ trials through the pubs, libraries and brothels on one notable day. Many readers lift this mighty tome but few put it down read much less understood. People employ guides, maps, lists and annotations to follow the complex plot through its 700 pages (Gabler Edition) making it their own personal odyssey and I must confess this novel defeated me at my first attempt (a second is pending).

After his early work to renew the Celtic myths, William Butler Yeats spent his latter years writing about Ireland’s transition to independence that painful yet joyous path to freedom in their own Nation. An ardent nationalist, he joined the IRA in his early years but distanced himself from political life as he grew older perhaps wiser until 1920. In 1922, Yeats (57) became a Senator in Irish Free State and he became a great advocate for the separation of Church and State. His poetry grew stronger in his latter years and his transition from a classical style to 20th Century modernism are often compared with his fellow artist Pablo Picasso’s transition in painting. Whether he truly made that leap into modernity is an academic trite, his words reverberate through time and his epitaph left us one last riddle.

Cast a cold Eye

On Life, on Death.

Horseman, pass by!

No where is Ireland’s love of the written word more evident than the Great Blasket Centre on the tip of the Dingle Peninsular dedicated to the extraordinary literary legacy of a small island community on Great Blasket Island and their struggle for survival. Tomás Ó Criomhthain wrote two incredible books (The Islandman and Island Cross Talk) about his life on the island, thoroughly absorbing and vivid tales of his way of life and the people with whom he shared the hardship of their remote island community. His success inspired other islanders to write about their lives, Peig Sayers and Muiris Ó Súilleabháin are the best known but dozens penned their tales in frenzy of writing as their island community withered in the late forties and early fifties. The final Great Blasket Island residents were evacuated in 1953, and their tale is told by Tomás’ son Seán in his book Lá dár Saol. Baile Átha Cliath Oifig an tSoláthair 1969 or, in English A Day in Our Life. Translated by Tim Enright. Oxford University Press, 1992. The shear volume of work from a community that never numbered more than 150 ensured that they will not be forgotten, helped to preserve the Irish language and the stories of their unique way of life. As Tomás Ó Criomhthain wrote in his final chapter:

No where is Ireland’s love of the written word more evident than the Great Blasket Centre on the tip of the Dingle Peninsular dedicated to the extraordinary literary legacy of a small island community on Great Blasket Island and their struggle for survival. Tomás Ó Criomhthain wrote two incredible books (The Islandman and Island Cross Talk) about his life on the island, thoroughly absorbing and vivid tales of his way of life and the people with whom he shared the hardship of their remote island community. His success inspired other islanders to write about their lives, Peig Sayers and Muiris Ó Súilleabháin are the best known but dozens penned their tales in frenzy of writing as their island community withered in the late forties and early fifties. The final Great Blasket Island residents were evacuated in 1953, and their tale is told by Tomás’ son Seán in his book Lá dár Saol. Baile Átha Cliath Oifig an tSoláthair 1969 or, in English A Day in Our Life. Translated by Tim Enright. Oxford University Press, 1992. The shear volume of work from a community that never numbered more than 150 ensured that they will not be forgotten, helped to preserve the Irish language and the stories of their unique way of life. As Tomás Ó Criomhthain wrote in his final chapter:

I have written minutely of much that we did, for it was my wish that somewhere there should be a memorial of it all, and I have done my best to set down the character of the people about me so that some record of us might live after us, for the like of us will never be again.